Ziprasidone

If one more person tells me ziprasidone "doesn't do anything," I'm going to choke them with the capsules. If it's never worked in your practice, how do you explain the numerous efficacy studies? All flukes? All of them? It couldn't be you?

Probably everyone has heard ziprasidone must be taken with food. But that's not to prevent nausea or protect the stomach lining, it's to get the drug to be absorbed.

You'll have to take my word for it right now that 120mg is the a base dose. (120mg ziprasidone=10mg olanzapine=3mg risperidone.) This is amazingly hard for psychiatrists to appreciate ("there are equivalences? And those are the doses??") But it's even harder to get them to understand the relationship to food: ziprasidone needs fat to be absorbed.

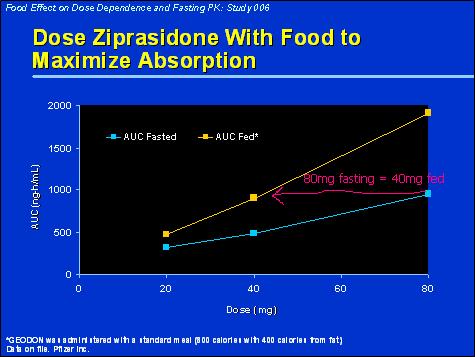

80mg on an empty stomach (blue line) gets you the equivalent of 40mg if taken with food. That's half the dose. In other words, if you dose your ziprasidone "all at night" (no food) then you're getting about half of what you thought you were. (In chronic dosing this will be less of a problem, but 30-50% increased absorption with food is a good guideline.)

Hospitals: they dose BID, which means morning and night, which means no food either time. Guess what happens (or doesn't).

BTW, crackers won't do it. The graph above is with 800 calories, 400 calories of fat. That's a meal, not juice.

If your doctor gives you less than 120mg and then gives up, he doesn't understand the proper dosing of ziprasidone. If he doesn't know about the importance of food, then you're in big trouble. Forget about reading journals, he's not even listening to the reps. (I know: because they're biased.)

I bring this up partly as a public service message, but also to explore the curious observation that even though many doctors know this already, they still don't dose with food. I can't imagine laziness is the answer. There is some weird thinking that this isn't relevant in the "real world" because food is weaker than medication. Drug-drug interactions matter; drug-food couldn't be important. And if it was really important, someone e would have mentioned it.

Everyone complains about diabetes and weight gain; here's a drug that likely doesn't have these problems. But because it doesn't have those toxicities, it therefore can't be "strong," or effective.

I'm not trying to advocate for ziprasidone. I'm pointing out that much of our perception of a treatment's efficacy can come simply from our mishandling of it; and to alert humanity to the inherent bias in ourselves. If we've never gotten ziprasidone to work, then not only do we think it doesn't work, but we think everyone who says it does work is a Pfizer schill.

Quetiapine had this problem, too. Six years ago, no one used quetiapine. Now everyone uses it. Did they improve it? No. It's marketing, but in reverse: Astra Zeneca didn't delude everyone into thinking it works when it doesn't; we deluded ourselves into thinking it didn't, when it did. So whose fault is that? Depakote: six years ago Depakote was untouchable, it was the king of bipolar treatment. Now? Did we get new data saying don't bother? Did they make the drug weaker? This is the key: the data that brings us today's conclusions is the exact same data that gave us the past's, opposite, conclusions. In other words, no one actually read the data; they based their conclusions on something else. Clinical experience? No.

The bias goes well beyond "Pfizer paid that doctor off"-- it comes from a belief system ("meds are life savers" vs. "meds are band-aids"; nature vs. nurture; your own race/gender; your family history of mental illness/drug abuse (or lack of it); your desire to be a "real doctor" etc, etc) that is much deeper and exerts a much stronger control over your thinking. To the exclusion of any new information.

And, of course, it's so much a part of you that you don't see it as a bias. And other people (patients) don't know it's there, so they're at the mercy of your unexamined assumptions.

The solution is exhausting, and no one will like it: constant critical re-evaluation of your beliefs. Both the science (as much of it as there is) and countertransference. And, most importantly, long looks at your own identity. How did you come up with it? Because, in fact, you did.

0 comments:

Post a Comment