Sunday, June 29, 2008

Clifford Stoll: 18 minutes with an agile mind

Posted by Lucy at 1:43 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Isabel Allende: Tales of passion

Posted by Lucy at 1:41 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Matthieu Ricard: Habits of happiness

Posted by Lucy at 1:39 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Barry Schwartz: The paradox of choice

Posted by Lucy at 1:36 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Larry Brilliant: The case for informed optimism

Posted by Lucy at 1:33 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Dan Dennett: Can we know our own minds?

Posted by Lucy at 1:31 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Howard Rheingold: Way-new collaboration

Posted by Lucy at 1:26 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Tony Robbins: Why we do what we do, and how we can do it better

Posted by Lucy at 1:14 PM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Peter Donnelly: How juries are fooled by statistics

Posted by Lucy at 1:11 PM 0 comments

Labels: presentations, statistics

How A New Paradigm is created

Posted by Lucy at 3:59 AM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy, presentations

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Hans Rosling: Global health expert; data visionary

Posted by Lucy at 2:50 AM 0 comments

Labels: presentations, statistics

Jill Bolte Taylor: My stroke of insight

Posted by Lucy at 2:06 AM 0 comments

Labels: beautiful brain, presentations

Friday, June 27, 2008

Slow Wave Sleep, Diabetes and Depression

Chris Ballas, M.D.

Friday, January 25, 2008

The issue with poor sleep is actually poor slow wave sleep. This is the specific subtype of overall sleep that is reduced in depression, even when the individual sleeps too much. Several studies have investigated the question, but a very recent one best illustrates the possible relationship between sleep and insulin/glucose control. The study took "normal" non-diabetic subjects, and selectively reduced their slow wave sleep-- the deep sleep that is often found in naps-- but left the light sleep and the REM sleep (the dreaming sleep that runs usually about 90 minutes per cycle in most people) and studied the effects on insulin release and insulin sensitivity.

Insulin sensitivity is how strongly a given amount of insulin will affect (i.e. lower) blood sugar. High sensitivity means that a given amount can reduce the glucose a lot; low sensitivity means that even in the presence of a lot of insulin, glucose doesn't go down (much.)

Type II diabetes is characterized not by insufficient insulin, but by insulin resistance. By way of analogy, your body is so used to having a lot of glucose in it that it doesn't respond to insulin as well as it did. The study found that thein the past; this is why it becomes more common in overweight and/or older individuals. Selective decrease in SWS-- even when total sleep time was the same--caused marked decreases in insulin sensitivity.

But there's a little more to it. Importantly, people who started with low amounts of SWS had the worst outcome when (what little they had) SWS was decreased.

This is what becomes relevant to people with depression. Depression, in general, reduces SWS even when total sleep time is intact. Obviously, it reduces it even more if overall sleep is reduced as well-- but even patients with hypersomnia ("atypical depression") have decreased SWS. We already know from unrelated studies that patients with depression have higher rates of diabetes-- and this may be one of the causes.

Next up are the medications, which, as a class, have little effect on totalsleep (may reduce it), reduce REM sleep, but increase SWS. This is particularly important for two reasons: first, it may have the potential to mitigate the effect of clinical depression on SWS and diabetes; second, a significant number of people on antidepressants also take sleeping pills-- pills, which, like antidepressants, typically suppress REM sleep but increase SWS and total sleep.

This is clearly not to say that sleeping pills will prevent diabetes; but it does suggest that sleep normalization in the context of the treatment of depression has an effect on the long term morbidity of depression--e.g. Diabetes.

Posted by Lucy at 7:07 PM 0 comments

Labels: depression, metabolic

Stress-absorbing magic vase from Japan

Serkan Toto June 9th, 2008

In case you are constantly stressed out and don’t have anyone to take it out on, the Sakebi no Tsufu comes to the rescue. This “shouting vase” from Japan is able to reduce stress if the owner holds it up to the mouth and clearly articulates his or her troubles.

The manufacturer claims it will magically suck up everything you say and keep it inside. I bet it does. The pot, which is made of thermoplastic, is able to turn yells into whispers through its special inner structure.

Posted by Lucy at 6:36 PM 0 comments

Labels: wish list

Teaching an Old Drug New Tricks

Chris Ballas, M.D.

Wednesday, April 02, 2008

There is some new data concerning an old drug. Mecamylamine is an old medication originally used to treat hypertension. It had numerous side effects, such as hypotension and sedation, and thus was not often used. It had a bit of a resurgence later on as an anti-smoking drug (it is a nicotine antagonist) but the overall efficacy was poor, and the side effects made it difficult to use. It was then suggested for use as an augmentation agent to traditional nicotine replacement drugs (gum, patch, etc.) It also has some off label and occasional use for autism, Tourette's, and OCD.

Recently, it has been tested for the treatment of depression. It was found to be better than placebo on the traditional rating scales for patients who had failed citalopram. While this is good, what made it particularly interesting is that the doses used were considerably less (by a factor of 10) than what had been used for hypertension—and at these low doses, mecamylamine only blocks central nervous system nicotinic receptors, not peripheral ones—resulting in much less sedation and hypotension.

It also had considerable efficacy in reducing irritability. Think what it may be like for a smoker to have a cigarette after a long plane ride.

All of this is well and good, but it brings up three questions:

First,why are we testing old medications? The answer probably has a lot to do with the current anti-Pharma climate. Antidepressants in general have already come under fire, both from researchers who have recently "discovered" they may not be very effective, as well as insurance companies, lawyers, and the media. Drug companies, even if they could, would be hard pressed to bring a novel compound for depression into an environment like this. It's easier to re-approve an existing drug. So you see repackaging of old drugs (consider Pristique), expanding the approval for medications already used in psychiatry (Abilify getting approval for adjunct use in MDD; Seroquel as monotherapy for bipolar depression), and looking through what already exists for new indications.

Second, if old drugs can be used for mood (in this case, specifically depression) then what does that say about depression itself? The norepinephrine hypothesis of depression was in vogue for some ten years, soon to be replaced by serotonin; but how do you explain how some people respond to Seroquel and others to Wellbutrin, when the two have nothing in common pharmacologically? More importantly, how do you explain it when the same person responds to both meds?

Third—and I've checked—there is no evidence so far that mecamylamine increases the suicide risk. (The same can be said of Seroquel and Abilify.) If mecamylamine does indeed get approval for depression, will it automatically inherit a black box warning for suicidality? The drug shares no chemical similarities to any existing antidepressant; but if we call it an antidepressant, does it inherit all the risks of one?

This isn't an idle question; warnings like this, attached to drugs which science has no reason to suspect—but which words indict—contribute to the environment I wrote about earlier, in which no one wants to try anything novel because it simply isn't worth it. And so we offer up the faint hope that old, barely tolerable blood pressure pills will save us.

Posted by Lucy at 6:06 PM 0 comments

Labels: antidepressants, anxiety, depression

Do Antidepressants Cause SUICIDE?

by Chris Ballas, M.D.

Monday, May 14, 2007

First, and most importantly, the answer is no. No single thing can cause a complex behavior such as suicide (or violence), and to say that a drug, or event, or illness made someone do something is simplistic and, well, wrong.

A more refined question would be whether antidepressants (or anything else) can contribute to the suicide process, move someone further along. Cocaine doesn't cause violence, but if you see a violent guy on cocaine, it's best to get out of the way.

The FDA, in 2002 and 2004, issued warnings about suicidal ideations in children who take antidepressants. Here are a couple of points for us to consider.

- These were kids

- The point of discussion is suicidal ideation, not suicide (death) per se.

The authors of a recent review of 29 studies found a similar small increase in risk.

Importantly, however, no actual suicides occurred.

They also analyzed whether or not the antidepressants were actually helpful to people, and weighted that finding against the risk of suicide. Their results determined the risk/reward ratio to be about 11:1, meaning that patients have 11 times better chance of being helped than hurt by antidepressants.

I should point out that, in my opinion, while there is absolutely no compelling evidence that these drugs promote suicidality, there is also a lack of compelling evidence indicating that they reduce suicidality. Nor would I expect there to be. Again, these drugs may change how someone feels, but there are a million steps between a feeling and an action. Which has the greater impact on suicidality: medications or the availability of a gun?

Asking the question simply, "do antidepressants cause suicide?" misses the meat of the argument. Cause? In whom? When, and under what circumstances? The real question is whether someone who is depressed is more likely to commit suicide off of the medicines than on them.

So while we ponder that question, let me offer a sobering statistic.

Only 30% of the people who committed suicide had seen a psychiatrist in the past year. That means 70% hadn't.

Source: JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

Clinical Response and Risk for Reported Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Pediatric Antidepressant Treatment, A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,Jeffrey A. Bridge et al,JAMA.2007;297:1683-1696.

Conclusions: Relative to placebo, antidepressants are efficacious for pediatric MDD, OCD, and non-OCD anxiety disorders, although the effects are strongest in non-OCD anxiety disorders, intermediate in OCD, and more modest in MDD. Benefits of antidepressants appear to be much greater than risks from suicidal ideation/suicide attempt across indications, although comparison of benefit to risk varies as a function of indication, age, chronicity, and study conditions.

__________________

Posted by Lucy at 5:44 PM 0 comments

Labels: antidepressants, depression, suicide

Friday, June 20, 2008

The Brain and its Function

Posted by Lucy at 6:15 PM 0 comments

Labels: beautiful brain, presentations

Sunday, June 15, 2008

The Psychological Maltreatment of Children—Technical Report

Pediatrics - Volume 109, Issue 4 (April 2002) - Copyright © 2002 American Academy of Pediatrics (Reprinted with permission), Steven W. Kairys MD, MPH Charles F. Johnson MD

ABSTRACT.

INTRODUCTION

Because pediatricians are concerned with the physical and emotional welfare of children, they are in a unique position to recognize and report psychological maltreatment. The pediatrician may be the only professional who has regular contact with maltreated children before they enter school. Pediatricians should be aware of risk factors in children and families that may predispose to psychological maltreatment and should recognize the types and consequences of psychological maltreatment. Early recognition and reporting of suspected psychological maltreatment to proper authorities, with the provision of therapeutic services, may prevent or ameliorate the consequences of psychological maltreatment. As with physical maltreatment, individual pediatricians' thresholds for concern will vary. State statutes on reporting document that only suspicion of psychological maltreatment is required to initiate a report to child protective services.

DEFINITION

Psychological maltreatment is a repeated pattern of damaging interactions between parent(s) and child that becomes typical of the relationship.[1] [2] [3] In some situations, the pattern is chronic and pervasive; in others, the pattern occurs only when triggered by alcohol or other potentiating factors. Occasionally, a very painful singular incident, such as an unusually contentious divorce, can initiate psychological maltreatment.[4] Psychological maltreatment of children occurs when a person conveys to a child that he or she is worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted, endangered, or only of value in meeting another's needs.[5] The perpetrator may spurn, terrorize, isolate, or ignore or impair the child's socialization.

If severe and/or repetitious, the following behaviors may constitute psychological maltreatment[6] :

Spurning (belittling, degrading, shaming, or ridiculing a child; singling out a child to criticize or punish; and humiliating a child in public).

Terrorizing (committing life-threatening acts; making a child feel unsafe; setting unrealistic expectations with threat of loss, harm, or danger if they are not met; and threatening or perpetrating violence against a child or child's loved ones or objects).

Exploiting or corrupting that encourages a child to develop inappropriate behaviors (modeling, permitting, or encouraging antisocial or developmentally inappropriate behavior; encouraging or coercing abandonment of developmentally appropriate autonomy; restricting or interfering with cognitive development).

Denying emotional responsiveness (ignoring a child or failing to express affection, caring, and love for a child).

Rejecting (avoiding or pushing away).

Isolating (confining, placing unreasonable limitations on freedom of movement or social interactions).

Unreliable or inconsistent parenting (contradictory and ambivalent demands).

Neglecting mental health, medical, and educational needs (ignoring, preventing, or failing to provide treatments or services for emotional, behavioral, physical, or educational needs or problems).

Witnessing intimate partner violence (domestic violence).

INCIDENCE AND CAUSAL FACTORS

As with other forms of child maltreatment, the true prevalence of psychological maltreatment is unknown. When it occurs exclusively, it may have more adverse impact on the child and on later adult psychological functioning than the psychological consequences of physical abuse, especially with respect to such measures as depression and self-esteem,[7] aggression, delinquency, or interpersonal problems.[8] Isolated psychological maltreatment has had the lowest rate of substantiation of any type of child maltreatment. In the 1997 Child Maltreatment national report,[1] psychological maltreatment (“emotional maltreatment”) was reported in 6.1% of 817 665 reports received from 43 states. In 1996, 15% of all registrations of maltreatment in England were for psychological maltreatment.[9] Parental attributes in cases reported for psychological maltreatment include poor parenting skills, substance abuse, depression, suicide attempts or other psychological problems, low self-esteem, poor social skills, authoritative parenting style, lack of empathy, social stress, domestic violence, and family dysfunction.[10] A number of studies have demonstrated that maternal affective disorder and/or substance abuse highly correlate to parent-child interactions that are verbally aggressive.[11] [12] At-risk children include children whose parents are involved in a contentious divorce; children who are unwanted or unplanned; children of parents who are unskilled or inexperienced in parenting; children whose parents engage in substance abuse, animal abuse, or domestic violence; and children who are socially isolated or intellectually or emotionally handicapped.[13]

CONSEQUENCES OF PSYCHOLOGICAL MALTREATMENT

Psychological maltreatment may result in a myriad of long-term consequences for the child victim.[14] A chronic pattern of psychological maltreatment destroys a child's sense of self and personal safety. This leads to adverse effects on the following[15] : Intrapersonal thoughts, including feelings (and related behaviors) of low self-esteem, negative emotional or life view, anxiety symptoms, depression, and suicide or suicidal thoughts.Emotional health, including emotional instability, borderline personality, emotional unresponsiveness, impulse control problems, anger, physical self-abuse, eating disorders, and substance abuse.Social skills, including antisocial behaviors, attachment problems, low social competency, low sympathy and empathy for others, self-isolation, noncompliance, sexual maladjustment, dependency, aggression or violence, and delinquency or criminality.Learning, including low academic achievement, learning impairments, and impaired moral reasoning.Physical health, including failure to thrive, somatic complaints, poor adult health, and high mortality. Similar patterns can be seen in children who are exposed to intimate partner violence.[16] Exposure to domestic violence by terrorizing, exploiting, and corrupting children increases childhood depression, anxiety, aggression, and disobedience in children.[16]

ASSESSMENT

A diagnosis of psychological maltreatment is facilitated when a documented event or series of events has had a significant adverse effect on the child's psychological functioning. Often it is a child's characteristics or emotional difficulties that first raise concern of psychological maltreatment. A psychologically abusive child-caregiver relationship can sometimes be observed in the medical office. More often, confirmation or suspicion of psychological maltreatment requires collateral reports from schools, other professionals, child care workers, and others involved with the family. Documentation of psychological maltreatment may be difficult. Physical findings may be limited to abnormal weight gain or loss. Ideally, the pediatrician who evaluates a child for psychological maltreatment will be able to demonstrate or opine that psychological acts or omissions of the caregiver have resulted (or may result) in significant damage to the child's mental or physical health. Documentation of the severity of psychological maltreatment on a standardized form (see Professional Education Materials for example) can assist practices to develop an accurate treatment plan in conjunction with (or cooperation with) other child health agencies. The severity of consequences of psychological maltreatment is influenced by its intensity, extremeness, frequency, and chronicity and mollifying or enhancing factors in the caregivers, child, and environment. Documentation must be objective and factual, including as many real quotes and statements from the child, the family, and other sources as possible. Descriptions of interactions, data from multiple sources, and changes in the behavior of the child are important. Ideally, the pediatrician will be able to describe the child's baseline emotional, developmental, educational, and physical characteristics before the onset of psychological maltreatment and document the subsequent adverse consequences of psychological maltreatment. In uncertain situations, referral to child mental health for additional evaluation is warranted. The stage of a child's development may influence the consequences of psychological maltreatment. Early identification and reporting of psychological maltreatment, with subsequent training and therapy for caregivers, may decrease the likelihood of untoward consequences. Because the major consequences of psychological maltreatment may take years to develop, delayed reporting of suspected psychological maltreatment (in an effort to document these adverse consequences more completely) may not be in the child's best interests.

PREVENTION

Psychological aggression (ie, parental controlling or correcting behavior that causes the child to experience psychological pain) is more pervasive than spanking.[8] A 1995 telephone survey suggested that by the time a child was 2 years old, 90% of families asked had used 1 or more forms of psychological aggression in the previous 12 months. This same survey revealed that 10% to 20% of toddlers and 50% of teenagers experience severe aggression (eg, cursing, threatening to send the child away, calling the child dumb or such other belittling names).[17] Therefore, prevention of psychological maltreatment may be the most important work of the pediatrician. Pediatricians can offer parents developmentally appropriate anticipatory guidance about the dangers of psychological aggression and maltreatment and model healthier parenting approaches to parents in the office at each visit. They may provide educational brochures to caregivers and inform parents very clearly that improper words and gestures or lack of supportive and loving words can greatly harm children. Most importantly, pediatricians can teach parents that their children need consistent love, acceptance, and attention. Community approaches, such as home visitation, have been shown to be highly successful in changing the behavior of parents at risk for perpetrating maltreatment.[18] Targeted programs for mothers with affective disorders and substance abuse have also been shown to be useful in preventing psychological maltreatment.[19] [20]

REFERENCES

1. National Center of Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Maltreatment. Washington, DC: National Center of Child Abuse and Neglect; 1997

2. Glaser D, Prior V. Is the term child protection applicable to emotional abuse? Child Abuse Rev. 1997;6:315–329

3. Buntain-Ricklefs JJ, Kemper KJ, Bell M, Babonis T. Punishments: what predicts adult approval? Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18:945–955 Abstract

4. Klosinski G. Psychological maltreatment in the context of separation and divorce. Child Abuse Negl. 1993;17:557–563 Abstract

5. Navarre EL. Psychological maltreatment: the core component of child abuse. In: Brassard MR, Germain R, Hart SN, eds. Psychological Maltreatment of Children and Youth. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1987:45–56

6. American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. Guidelines for Psychosocial Evaluation of Suspected Psychological Maltreatment in Children and Adolescents. Chicago, IL: American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children; 1995

7. Claussen AH, Crittenden PM. Physical and psychological maltreatment: relations among types of maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 1991;15:5–18 Abstract

8. Vissing YM, Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Harrop JW. Verbal aggression by parents and psychosocial problems of children. Child Abuse Negl. 1991;5:223–238 Abstract

9. Doyle C. Emotional abuse of children: issues for intervention. Child Abuse Rev. 1997;6:330–342

10. Garbarino J, Vondra J. Psychological maltreatment: issues and perspectives. In: Brassard MR, Germain R, Hart SN, eds. Psychological Maltreatment of Children and Youth. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1987:25–44

11. Kelley JT. Stress and coping behaviors of substance abusing mothers. J Soc Pediatr Nurs. 1998;3:103–110 Abstract

12. Tracy EM. Maternal substance abuse. Protecting the child, preserving the family. Soc Work. 1994;39:534–540 Abstract

13. Hart SN, Brassard MR. A major threat to children's mental health. Psychological maltreatment. Am Psychol. 1987;42:160–165 Citation

14. Briere J, Runtz M. Differential adult symptomotology associated with three types of child abuse histories. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14:357–364 Abstract

15. Hart SN, Binggeli NJ, Brassard MR. Evidence for the effects of psychological maltreatment. J Emot Abuse. 1998;1:27–58

16. Hughes HM, Graham-Bermann SA. Children of battered women: impact of emotional abuse on adjustment and development. J Emot Abuse. 1998;1:23–50

17. Straus MA, Field C. Psychological Aggression By American Parents: National Data on Prevalence, Chronicity, and Severity. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 2000

18. Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR Jr, et al. Long term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: a fifteen year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997;278:637–643 Abstract

19. Keen J, Alison LH. Drug abusing parents: key points for health professionals. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:196–199 Citation

20. Dore M, Doris J. Preventing child placement in substance abusing families: research informed practice. Child Welfare. 1998;77:407–426 Abstract SUGGESTED READING

21. American Humane Association. Child abuse fact sheets. American Humane Association Web site. Available at: http://www.amerhumane.org

22. Brassard MR, Hart SN. Emotional Abuse: Words Can Hurt. Chicago, IL: National Committee to Prevent Child Abuse; 1987

23. Harris PL. Children and Emotion: The Development of Psychological Understanding. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1989

24. Hart SN, Brassard MR, Karlson H. Psychological maltreatment. In: Briere J, Berliner L, Bulkley J, Jenny C, Reid T, eds. The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1996:72–89 (new edition in press)

25. Hart SN, Germain RB, Brassard MR. The challenge: to better understand and combat psychological maltreatment of children and youth. In: Brassard MR, Germain R, Hart SN, eds. Psychological Maltreatment of Children and Youth. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1987:3–24

26. Iwaniec D. Overview of emotional maltreatment and failure-to-thrive. Child Abuse Rev. 1997;6:370–388

27. O'Hagan KP. Emotional and psychological abuse: problem of definition. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:449–461 Abstract

28. Sanchez-Hucles JV. Racism: emotional abusiveness and psychological trauma for ethnic minorities. J Emot Abuse. 1998;1:69–87 PATIENT EDUCATION MATERIALS

29. Prevent Child Abuse America. 200 S Michigan Ave, 17th Floor, Chicago, IL 60604. 312/663–3520. Available at: http://www.preventchildabuseamerica.org PROFESSIONAL

EDUCATION MATERIALS

30. National Clearing House on Child Abuse and Neglect Information. 330 C St SW, Washington, DC 20447. 800/ 394–3366. Available at: http://www.calib.com/nccanch/index.htm

31. Suspect Psychological Maltreatment Reporting Form. Form created by Charles F. Johnson, MD, Child Abuse Program at Children's Hospital, 700 Children's Dr, Columbus, OH 43205.

E-mail: cjohnson@chi.osu.edu The recommendations in this statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

Copyright © 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Posted by Lucy at 4:25 AM 0 comments

Labels: abuse

Memory's Seven Sins

Schacter's Seven Sins of Memory

Notes on Daniel L. Schacter (1999) "The Seven Sins of Memory: Insights From Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience" (Full text) American Psychologist Vol. 54. No. 3, 182-203

This is a 22-page review paper that summarises seven ways in which human memory can fail, and argues that despite the problems they cause, they are all side-effects of positive features of memory. In other words, if we could get rid of these forgetting and biasing processes, we would actuallly be worse off as our minds were flooded with irrelevant and confusing information. Schacter expanded this paper into a 2001 book.

My own interest is in bias, rather than in the biological basis for memory or the relation between the different memory systems. This paper is useful for students of bias firstly because it sets out ways in which memory can be biased, and secondly because it illustrates how some human irrationality can be explained as adaptive. In the notes below I've made use of a couple of Schacter's other papers which are cited.

The Seven Sins

"The first 3 sins involve different types of forgetting, the next 3 refer to different types of distortions, and the final sin concerns intrusive recollections that are difficult to forget." - from the abstract.

Transience

This is straightforward forgetting: the decay of recalled information over time. The brain has multiple memory systems, with different forgetting characteristics.

Absent-mindedness

"[I]ncidents of forgetting associated with lapses of attention during encoding or

during attempted retrieval can be described as errors of absent-mindedness"

Blocking

"When people are provided with cues that are related to a sought-after item, but are nonetheless unable to elicit it, a retrieval block has occurred", e.g. tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon

Misattribution

Schacter identifies three kinds of misattribution:

- Source confusion: "people may remember correctly an item or fact from a past experience but misattribute the fact to an incorrect source" e.g. eyewitnesses confusing where or when they saw a particular person; subjects confusing whether they saw something in real life or on television; confusions between imagination and memory

- Cryptomnesia: "an absence of any subjective experience of remembering. People sometimes misattribute a spontaneous thought or idea to their own imagination, when in fact they are retrieving it—without awareness of doing so—from a specific prior experience" e.g. unconscious plagiarism

- False recall and false recognition: when individuals falsely recall or recognize items or events that never happened. In some experiments, subjects show just as much confidence in their false recall as in their correctly recalled items.

A paper in which Schacter goes into more detail on misattribution is D. L. Schacter and C. S. Dodson (2001) "Misattribution, false recognition and the sins of memory." (Full text PDF) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences Sep 29;356(1413):1385-93.

Suggestibility

"Suggestibility in memory refers to the tendency to incorporate information provided by others, such as misleading questions, into one's own recollections". Suggestibility is really a kind of misattribution. Schacter uses the term "suggestibility" for misattribution where the misattributed information is suggested by another person. e.g. Loftus "lost in the mall" study. Repeated and/or specific questions can cause the subject to vividly imagine an event, and then they can misattribute this vivid mental image as a memory.

Bias

"Bias refers to the distorting influences of present knowlege, beliefs, and feelings on recollection of previous experiences" Bias is discussed briefly in the 1999 paper, but at greater length in Schacter's 2001 book.

- Consistency bias: memories of past attitudes distorted to be more similar to present attitudes. (including distortion of memory by cognitive dissonance)

- Change bias: people who have worked hard to improve their study skills distort their memory of how good they were before the course downwards (justification-of-effort bias?)

- Stereotypical bias: e.g. racial and gender biases in memory, e.g. made-up "black" names are more frequently falsely remembered as names of criminals than "white" names

- Hindsight bias: recollections of past events are filtered by current knowledge;

- Egocentric bias: individuals recall the past in a self-enhancing manner; e.g. fishermen "remembering" catching bigger and bigger fish.

A more recent paper about bias is Daniel L. Schacter, Joan Y. Chiao, Jason P. Mitchell (2003) "The Seven Sins of Memory. Implications for Self" (Full text, subscription required) Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1001 (1), 226–239.

Persistence

"Persistence involves remembering a fact or event that one would prefer to forget. Persistence is revealed by intrusive recollections of traumatic events, rumination over negative symptoms and events, and even by chronic fears and phobias." Depressed subjects show greater memory for negative events and stimuli (a persistance bias?).

Posted by Lucy at 3:11 AM 0 comments

Labels: beautiful brain

Fallacies

Formal fallacies

Formal fallacies are arguments that are fallacious due to an error in their form or technical structure. All formal fallacies are specific types of non sequiturs.

- Appeal to probability: because something could happen, it is inevitable that it will happen. This is the premise on which Murphy's Law is based.

- Argument from fallacy: if an argument for some conclusion is fallacious, then the conclusion must necessarily be false.

- Bare assertion fallacy: premise in an argument is assumed to be true purely because it says that it is true.

- Base rate fallacy: using weak evidence to make a probability judgment without taking into account known empirical statistics about the probability.

- Conjunction fallacy: assumption that specific conditions are more probable than a single general one.

- Correlative based fallacies

- Denying the correlative: where attempts are made at introducing alternatives where there are none

- Suppressed correlative: where a correlative is redefined so that one alternative is made impossible

- Fallacy of necessity: a degree of unwarranted necessity is placed in the conclusion based on the necessity of one or more of its premises

- False dilemma (false dichotomy): where two alternative statements are held to be the only possible options, when in reality there are several

- If-by-whiskey: An answer that takes side of the questioner's suggestive question

- Ignoratio elenchi (irrelevant conclusion or irrelevant thesis)

- Homunculus fallacy: where a "middle-man" is used for explanation, this usually leads to regressive middle-man explanations without actually explaining the real nature of a function or a process

- Masked man fallacy: the substitution of identical designators in a true statement can lead to a false one

- Naturalistic fallacy: a fallacy that claims that if something is natural, then it is "good" or "right"

- Nirvana fallacy: when solutions to problems are said not to be right because they are not perfect

- Negative proof fallacy: that because a premise cannot be proven true, that premise must be false

- Package-deal fallacy: when two or more things have been linked together by tradition or culture are said to stay that way forever

Propositional fallacies

Propositional fallacies:

- Affirming a disjunct: concluded that one logical disjunction must be false because the other disjunct is true.

- Affirming the consequent: the antecedent in an indicative conditional is claimed to be true because the consequent is true. Has the form if A, then B; B, therefore A

- Denying the antecedent: the consequent in an indicative conditional is claimed to be false because the antecedent is false; if A, then B; not A, therefore not B

Quantificational fallacies

Quantificational fallacies:

- Existential fallacy: an argument has two universal premises and a particular conclusion, but the premises do not establish the truth of the conclusion

- Illicit conversion: the invalid conclusion that because a statement is true, the inverse must be as well

- Proof by example: where things are proved by giving an example

Formal syllogistic fallacies

Syllogistic fallacies are logical fallacies that occur in syllogisms.

- Affirmative conclusion from a negative premise

- Fallacy of exclusive premises: a categorical syllogism that is invalid because both of its premises are negative

- Fallacy of four terms: a categorical syllogism has four terms

- Illicit major: a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its major term is undistributed in the major premise but distributed in the conclusion

- Illicit minor: a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its minor term is undistributed in the minor premise but distributed in the conclusion.

- Fallacy of the undistributed middle: the middle term in a categorical syllogism is not distributed

- Categorical syllogism: an argument with a positive conclusion, but one or two negative premises

Informal fallacies

Informal fallacies are arguments that are fallacious for reasons other than structural ("formal") flaws.

- Argument from repetition (argumentum ad nauseam)

- Appeal to ridicule: a specific type of appeal to emotion where an argument is made by presenting the opponent's argument in a way that makes it appear ridiculous

- Argument from ignorance ("appeal to ignorance"): The fallacy of assuming that something is true/false because it has not been proven false/true. For example: "The student has failed to prove that he didn't cheat on the test, therefore he must have cheated on the test."

- Begging the question ("petitio principii"): where the conclusion of an argument is implicitly or explicitly assumed in one of the premises

- Burden of proof

- Circular cause and consequence

- Continuum fallacy (fallacy of the beard)

- Correlation does not imply causation (cum hoc ergo propter hoc)

- Equivocation

- Fallacies of distribution

- Division: where one reasons logically that something true of a thing must also be true of all or some of its parts

- Ecological fallacy

- Fallacy of many questions (complex question, fallacy of presupposition, loaded question, plurium interrogationum)

- Fallacy of the single cause

- Historian's fallacy

- False attribution

- False compromise/middle ground

- Gambler's fallacy: the incorrect belief that the likelihood of a random event can be affected by or predicted from other, independent events

- Incomplete comparison

- Inconsistent comparison

- Intentional fallacy

- Loki's Wager

- Lump of labour fallacy (fallacy of labour scarcity, zero-sum fallacy)

- Moving the goalpost

- No true Scotsman

- Perfect solution fallacy: where an argument assumes that a perfect solution exists and/or that a solution should be rejected because some part of the problem would still exist after it was implemented

- Post hoc ergo propter hoc: also known as false cause, coincidental correlation or correlation not causation.

- Proof by verbosity (argumentum verbosium)

- Psychologist's fallacy

- Regression fallacy

- Reification (hypostatization)

- Retrospective determinism (it happened so it was bound to)

- Special pleading: where a proponent of a position attempts to cite something as an exemption to a generally accepted rule or principle without justifying the exemption

- Suppressed correlative: an argument which tries to redefine a correlative (two mutually exclusive options) so that one alternative encompasses the other, thus making one alternative impossible

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Wrong direction

Faulty generalizations

- Accident (fallacy): when an exception to the generalization is ignored

- Cherry picking

- Composition: where one infers that something is true of the whole from the fact that it is true of some (or even every) part of the whole

- Dicto simpliciter

- Converse accident (a dicto secundum quid ad dictum simpliciter): when an exception to a generalization is wrongly called for

- False analogy

- Hasty generalization (fallacy of insufficient statistics, fallacy of insufficient sample, fallacy of the lonely fact, leaping to a conclusion, hasty induction, secundum quid)

- Loki's Wager: insistence that because a concept cannot be clearly defined, it cannot be discussed

- Misleading vividness

- Overwhelming exception

- Spotlight fallacy

- Thought-terminating cliché: a commonly used phrase, sometimes passing as folk wisdom, used to quell cognitive dissonance.

Red herring fallacies

A red herring is an argument, given in response to another argument, which does not address the original issue. See also irrelevant conclusion

- Ad hominem: attacking the personal instead of the argument. A form of this is reductio ad Hitlerum.

- Argumentum ad baculum ("appeal to force", "appeal to the stick"): where an argument is made through coercion or threats of force towards an opposing party

- Argumentum ad populum ("appeal to belief", "appeal to the majority", "appeal to the people"): where a proposition is claimed to be true solely because many people believe it to be true

- Association fallacy & Guilt by association

- Appeal to authority: where an assertion is deemed true because of the position or authority of the person asserting it

- Appeal to consequences: a specific type of appeal to emotion where an argument concludes a premise is either true or false based on whether the premise leads to desirable or undesirable consequences for a particular party

- Appeal to emotion: where an argument is made due to the manipulation of emotions, rather than the use of valid reasoning

- Appeal to fear: a specific type of appeal to emotion where an argument is made by increasing fear and prejudice towards the opposing side

- Wishful thinking: a specific type of appeal to emotion where a decision is made according to what might be pleasing to imagine, rather than according to evidence or reason

- Appeal to spite: a specific type of appeal to emotion where an argument is made through exploiting people's bitterness or spite towards an opposing party

- Appeal to flattery: a specific type of appeal to emotion where an argument is made due to the use of flattery to gather support

- Appeal to motive: where a premise is dismissed, by calling into question the motives of its proposer

- Appeal to novelty: where a proposal is claimed to be superior or better solely because it is new or modern

- Appeal to poverty (argumentum ad lazarum)

- Appeal to wealth (argumentum ad crumenam)

- Argument from silence (argumentum ex silentio)

- Appeal to tradition: where a thesis is deemed correct on the basis that it has a long standing tradition behind it

- Chronological snobbery: where a thesis is deemed incorrect because it was commonly held when something else, clearly false, was also commonly held

- Genetic fallacy

- Judgmental language

- Poisoning the well

- Sentimental fallacy: it would be more pleasant if; therefore it ought to be; therefore it is

- Straw man argument

- Style over substance fallacy

- Texas sharpshooter fallacy

- Two wrongs make a right

- Tu quoque

Conditional or questionable fallacies

Posted by Lucy at 2:40 AM 0 comments

Labels: philosophy

Ziprasidone

If one more person tells me ziprasidone "doesn't do anything," I'm going to choke them with the capsules. If it's never worked in your practice, how do you explain the numerous efficacy studies? All flukes? All of them? It couldn't be you?

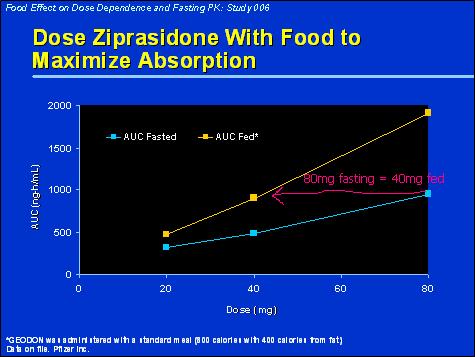

Probably everyone has heard ziprasidone must be taken with food. But that's not to prevent nausea or protect the stomach lining, it's to get the drug to be absorbed.

You'll have to take my word for it right now that 120mg is the a base dose. (120mg ziprasidone=10mg olanzapine=3mg risperidone.) This is amazingly hard for psychiatrists to appreciate ("there are equivalences? And those are the doses??") But it's even harder to get them to understand the relationship to food: ziprasidone needs fat to be absorbed.

80mg on an empty stomach (blue line) gets you the equivalent of 40mg if taken with food. That's half the dose. In other words, if you dose your ziprasidone "all at night" (no food) then you're getting about half of what you thought you were. (In chronic dosing this will be less of a problem, but 30-50% increased absorption with food is a good guideline.)

Hospitals: they dose BID, which means morning and night, which means no food either time. Guess what happens (or doesn't).

BTW, crackers won't do it. The graph above is with 800 calories, 400 calories of fat. That's a meal, not juice.

If your doctor gives you less than 120mg and then gives up, he doesn't understand the proper dosing of ziprasidone. If he doesn't know about the importance of food, then you're in big trouble. Forget about reading journals, he's not even listening to the reps. (I know: because they're biased.)

I bring this up partly as a public service message, but also to explore the curious observation that even though many doctors know this already, they still don't dose with food. I can't imagine laziness is the answer. There is some weird thinking that this isn't relevant in the "real world" because food is weaker than medication. Drug-drug interactions matter; drug-food couldn't be important. And if it was really important, someone e would have mentioned it.

Everyone complains about diabetes and weight gain; here's a drug that likely doesn't have these problems. But because it doesn't have those toxicities, it therefore can't be "strong," or effective.

I'm not trying to advocate for ziprasidone. I'm pointing out that much of our perception of a treatment's efficacy can come simply from our mishandling of it; and to alert humanity to the inherent bias in ourselves. If we've never gotten ziprasidone to work, then not only do we think it doesn't work, but we think everyone who says it does work is a Pfizer schill.

Quetiapine had this problem, too. Six years ago, no one used quetiapine. Now everyone uses it. Did they improve it? No. It's marketing, but in reverse: Astra Zeneca didn't delude everyone into thinking it works when it doesn't; we deluded ourselves into thinking it didn't, when it did. So whose fault is that? Depakote: six years ago Depakote was untouchable, it was the king of bipolar treatment. Now? Did we get new data saying don't bother? Did they make the drug weaker? This is the key: the data that brings us today's conclusions is the exact same data that gave us the past's, opposite, conclusions. In other words, no one actually read the data; they based their conclusions on something else. Clinical experience? No.

The bias goes well beyond "Pfizer paid that doctor off"-- it comes from a belief system ("meds are life savers" vs. "meds are band-aids"; nature vs. nurture; your own race/gender; your family history of mental illness/drug abuse (or lack of it); your desire to be a "real doctor" etc, etc) that is much deeper and exerts a much stronger control over your thinking. To the exclusion of any new information.

And, of course, it's so much a part of you that you don't see it as a bias. And other people (patients) don't know it's there, so they're at the mercy of your unexamined assumptions.

The solution is exhausting, and no one will like it: constant critical re-evaluation of your beliefs. Both the science (as much of it as there is) and countertransference. And, most importantly, long looks at your own identity. How did you come up with it? Because, in fact, you did.Posted by Lucy at 12:25 AM 0 comments

Labels: antipsychotics

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Can An Antipsychotic be an Antidepressant?

November 3, 2006

The Charade is Revealed-- We Are Doomed

Here's a question: can an antipsychotic be an antidepressant? Why, or why not?

The correct answer is that the question is invalid, because there is no such thing as an "antipsychotic" or an "antidepressant." We (should) define them based on what they do, not what they are. Therefore, Wellbutrin and Effexor are both antidepressants if and only if they both treat depression-- not because of some element of their pharmacologies, which are anyway different. Strattera, on the other hand-- which has a pharmacology (in some ways) similar to Effexor-- is not an antidepressant, only because it doesn't treat depression.

Following, just because something is called an antidepressant, or antihypertensive, it doesn't necessarily take on all the other properties or side effects of the others in its "class." Not all "antidepressants" have withdrawal syndromes (only SSRIs do). Not all antihypertensives cause urination (only diuretics do.) You wouldn't dare put a "class labeling" on "antihypertensives" of "diuresis."

So you see where I'm going with this-- except you don't.

I've previously yelled about the inanity of "antipsychotic induced diabetes" or "antidepressant induced mania" when they ignore pharmacologies, doses, and, of course, actual data.

But today I saw something that I now understand to be one of the signs of the Apocalypse. It is the new package insert of Seroquel, which just got a new indication for the treatment of bipolar depression. The new PI reads:

Suicidality in children and adolescents - antidepressants increased the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior (4% vs 2% for placebo) in short-term studies of 9 antidepressant drugs in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Patients started on therapy should be observed closely for clinical worsening, suicidality, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation and communication with the prescriber. SEROQUEL® is not approved for use in pediatric patients. (see Boxed Warning)

Stating the obvious: in none of these 9 studies was any patient actually ever on Seroquel; Seroquel itself is not associated with a risk of suicide; it's not even been tested for major depressive disorder; and, well, this isn't very rigorous science, is it?

Just because a is now called an antidepressant, it carries the same risk as the SSRIs? (Whether even SSRIs have this risk is besides the point.) Isn't that, well, racist?

This is not really about preventing suicide. If we were worried about suicide, really, then why 24 hours before the FDA posted this warning, no one cared about Seroquel's doubling of the suicide rate? Oh, because it doesn't actually double the suicide rate? Die.

So the game is clearly not about science, it's about politics, it's about liability, it's about money.

If this was honestly about about protecting children from suicide, we'd shrug our shoulders and say, "well, they're just very, very cautious, so we'll be careful and keep going." But that's not what this is. What this is factually inaccurate, misleading, and therefore more dangerous, more harmful. In a simple example, this warning protects no one for a risk of suicide-- no potentially suicidal patient is going to look at this and say, "well, crap, I'm not taking this." But it may prevent someone from taking it when they could actually benefit. See?

This is Structuralism gone very badly awry, Saussure just bought a pick axe and he's come looking for us all.

Posted by Lucy at 11:35 PM 0 comments

Labels: antidepressants, antipsychotics

Insults vs. Narcissistic injuries

The Last Psychiatrist - January 9, 2007

Narcissistic injuries have nothing to do with sadness. They are always and only about rage.

The narcissist says, "I exist." A narcissistic injury is you showing him that he does not exist in your life. Kicking him in the teeth and telling him he is a jerk is not a narcisstic injury-- because he must therefore exist.

Let's say I'm a narcissist, and you send me a 10 page letter explaining why I suck, I'm a jerk, I'm an idiot; you attack my credibility, my intelligence; and you even provide evidence for all of this, college transcripts, records from the Peters Institute, you criticize my penis size, using affidavits from past and future girlfriends-- all of this hurts me, but it is not a narcissistic injury.

A narcissistic injury would be this: I expect you to write such a letter, and you don't bother.

This is most easily seen in the failing marriage of a narcissist.

The reason it's important is because the reaction of the narcissist to either "insult" is different. In the first example, he will be sad and hurt, but he will yell back, insult you, or cry and beg forgiveness or mercy--he will respond-- maintain the relationship. He'll say and do outrageous things that he knows will cause you to respond again, to prolong your connections, even if they cause him misery. He doesn't care that it makes you and him miserable-- he cares only that there is a you and him.

But in the latter case where you ignore him, humiliate him-- an actual narcissisitic injury-- he will want to kill you.

----

And before everyone flames me, I am not trying to give a scientific explanation of the pathogenesis of narcissism. This is simply one man's opinion of how we can specify what it is, and what it may predict, past or future. Nor am I suggesting this isn't "treatable"-- anyone can change. It may not be easy, but it is always possible.

And I also do not mean to imply that all narcissists will kill everyone who injures them. The point is rage. They may never act on it, or they may break a window, or attempt suicide, etc.

January 5, 2007

Borderline

Narcissism- what I believe to be the primary disease of our times-- is one side of a coin. The other side-- the narcissist's enabler-- is the borderline.

If the analogy for narcissism is "being the main character in their own movie," then the analogy for borderline is being an actress.

Note the difference: the narcissist is a character: an invented but well scripted, complete with backstory, identity. The narcissist is trying to be something-- which already has a model. Perhaps he thinks himself an artist type, or a tough guy, or the type interested in spiritualism, or like the guy in the Matrix. Types, characters. The borderline is no one: the borderline waits for the script to define her.

Her? Yes. Narcissists are mostly hes, and borderlines hers. (Not always, sure.)

The classic description includes: intense, unstable relationships; emotional lability; fear of abandonment. The borderline has no true sense of self.

Ironically, the borderline is a borderline only in relationship to other people. The borderline has a problem with identity only because other people in the world have stronger identities. Your Dad wants you to be one way, so you do it. Your boyfriend wants a different woman; so you do it. Your husband wants something else; so you do it. Who the hell are you, really? You have no idea, because you are always molding yourself based on the dominant personality in your life.

This si done mostly out of fear of abandonment: if you don't "be" the person they want, then they'll leave you, and then what? (Borderlines don't end relationships-- they end relationships for another relationship.)

The narcissist creates an identity, then tries to force everyone else to buy into it. The borderline waits to meet someone, and then constructs a personality suitable to that person.

If a borderline is dating a guy who loves the Dallas Cowboys, then for sure, she will love the Dallas Cowboys. If, however, she breaks up with him, and then dates a guy who loves the Giants, then she'll love the Giants. But here's what makes her a borderline: she will actually believe the Giants are better. She's not lying, and she's not doing it for him; she actually thinks she thinks it's true. Everyone else on the outside sees that it is obviously a function of whom she's dating, but she is sure she came up with it on her own. And she's not play acting: at that moment that she believes, with every fiber of her being, that the Giants are better.

Here's the ironic part: if a borderline was shipwrecked on a desert island with no one around, she'd develop a real identity, of her own, not a reaction to other people. Sorry, that's not the ironic part, this is: she'd become a narcissist.

The bordeline has external markings of identity: tattoos, changing hair colors, clothes. You may recall I said almost the same thing about the narcissist: the difference is, of course, the borderline changes her image as she changes her identity-- in other words, as she cahges the dominant personality in her life; but the narcissist crafts a look, an identity, which he then defends at all costs: "I would sooner eat fire ants than shave my mustache." Of course. Of course.

All those silly movies about a woman moving away, or to the big city, and she "finds herself:" that's a borderline becoming a narcissist.

If you look back on past long term relationships you've had, and are completely perplexed as to what on earth you ever saw in each of those people that kept you with them for a year; well, there you go.

This is why narcissists marry borderlines, and not other narcisstists. Two narcissists simply can't get along: who is the main character? Meanwhile, two borderlines can't be with each other-- who supplies the identity? The narcissist thrives with the borderline because she provides for him the validation that he is, in fact, the lead; the borderline thrives with the narcissist because he defines her. And, as she will tell you every single time, without fail: "you don't know him like I do." Everyone else judges his behavior; but the borderline is judging his version of himself that she has accepted.

Go back to my white high heel shoes example. The narcissist demands his woman wear white high heel pumps not because hem ay like them himself-- he might or might not-- but because he is the type of man that would be with the type of woman who wears white pumps. He thinks he's the sophisticated, masculine man of the 1980s, so she damn well better be Kim Bassinger from 9 1/2 Weeks. Blonde hair, white pumps. She could weight 400lbs, that's not the point (though it will become one later.) So she wears the shoes, and starts to believe she likes them, starts to believe that she is that woman. He reinforces this with certain behaviors or language towards her (he'll open the door for her, push her chair in, etc. You say, "well, what's wrong with that? Nothing, except that he ALSO beats her when she doesn't wear the shoes.)

It's almost battered-wife syndrome: what keeps her with tat maniac is that when he's not beating her, it seems like he is actually being kind to her, so great is the difference between being beaten and simply not being beaten. Meanwhile everything he does wrong has an external explanation: it was the alcohol, he's under stress, etc. And she's doing this rationalizing for herself, not for him, because it is vital to her own psychological survival that he actually be who he says he is, that he actually have a stable identity that things happen to, because her identity depends on his being a foundation.

That's why the therapist has to maintain such neutrality, consistency in the sessions. It's not just to avoid conflicts; by being the most dominant (read: consistent) personality, the borderline can begin to construct one for herself using the blueprints of yours as a guide.

If the borderline sounds like a 15 year old girl, that's because that's what she is. The difference, of course, is the actual 15 year old girl is supposed to be flaky, testing identities and philosophies and looks until she finally lands on the one that's "her." But if you're 30 and doing that, well...

--------

(BTW, if you want to understand the mystery of women's addiction to shoes, here's my take: shoes are the article of clothing that represent possibility. Each shoe is a different look, a different character, and she can select "who" she wants to be that day. You might not notice the difference, but she feels it. This is not borderline-- it's normal, but it's normal because the shoe changes and the rest of her doesn't.)

March 7, 2007

The Psychological Uncertainty Principle

cat

A commenter, who I believe is a physics undergrad (his blog here) emailed me some of his thoughts on narcissism, and wrote:

...those studies where people rank each other in a room for different attributes having never met them... I think what's going on is we assign people personalities based on how they look and force them to become a certain thing, creating a whole custom world for them...

which puts the idea of "profiling" on its head. Do we actually ever "figure people out," or do we change them into what we think they are by the act of engaging in a relationship (on any level) with them? It sounds a lot like a psychological version of quantum entanglement:

When two systems, of which we know the states by their respective representatives, enter into temporary physical interaction due to known forces between them, and when after a time of mutual influence the systems separate again, then they can no longer be described in the same way as before, viz. by endowing each of them with a representative of its own... By the interaction the two representatives have become entangled.

Which, unfortunately, sounds a lot like this (p. 236):

The unreflective consciousness does not apprehend the person directly or as its object; the person is presented to consciousness in so far as the person is an object for the Other. This means that all of a sudden I am conscious of myself escaping myself, not in that I am the foundation of my own nothingness but in that I have my foundation outside myself. I am for myself only as I am a pure reference for the Other.

You can't know who a person is without relating to them, and once you do that, you irrevocably change them.

Only in relationship to another do you get defined. Sometimes you can do it with your God; but either way, any adjective has to be placed on you by someone else. Are you brave? Strong? funny, stupid, nervous? All that comes from someone else. So when someone relates to you, they define you. You can try to control this-- hence the narcissist preying on the borderline to get her to see him the way he wants to be seen-- but ultimately it's up to the other person.

So we're are, or become, whatever a person thinks we are? No, it's worse than that-- we want to be what they think we are. That's why we maintain the relationship, otherwise we'd change it. ("I divorced her because I didn't like who I became.")

We do it because it is easier, and it serves us. You're kind because he sees you as kind-- which in turn allows him to be seen as someone who can detect kindness. And you accept that you're kind-- or mean/vulnerable/evil/brilliant-- because it serves you-- there's some gain there. But a strong person accepts that on the one hand the other person gives you definition, and on the other hand you are completely undefinable, free, at any moment, to redefine yourself. You can defy him, biology, environment and be anything.

You say: but I can't be a football star just because I want to. But that's wanting someone else to see you in a certain way. Do you want to play ball? Go play ball. "But I won't get on the team." Again, that's wanting to change someone else. Change you first.

But what about-- identity? That's the mistake, that's bad faith. Thinking that our past is us; what we did defines us. Our past can be judged-- what else is there to judge?- but it can't-- shouldn't-- define us, because at any moment we are free to change into something, anything else. And so, too, we can be judged for not changing.

Ultimately, you are responsible for everything you do and think. Not for what happens to you, but for how you choose to react. Nothing else made you be. Nothing else made you do.

Trinity said it best: The Matrix cannot tell you who you are.

Posted by Lucy at 11:00 PM 0 comments

Labels: personality